“Crystallizing Experiences”: The Importance of Fiction and How “The Chosen” TV Series Ended up in My Dissertation

I’ve been meaning to write this for over a year now, but teaching during a pandemic (and writing a book about combating teacher burnout — which also mentions The Chosen!) rather derailed my plans. Now that season 2 of The Chosen has aired, and new criticisms of it trying to “rewrite Scripture” have surfaced, I figured it was time to share why I think this TV show could play an important role in evangelization and how on earth it ended up in my dissertation for my doctorate in education.

My Dissertation Topic

My dissertation (defended June 1, 2020) was entitled Engendering Empathy for Immigrants in Middle Grade Readers Through Culturally Relevant YA Literature. (YA stands for Young Adult. For the purpose of this study, I defined young adult literature as books aimed at teens and tweens.) That topic may appear to have nothing in common with a TV show about Jesus and His disciples, but what I discovered during my qualitative research is that the why behind my research questions can also explain why The Chosen has been having such a profound impact on people.

My Research Questions

As an English teacher, I was interested in discovering how reading a work of historical fiction as part of a literature course impacted students who were studying that same historical period in their history course. I conducted my research at a school where eighth graders studied the Great Immigration period of the United States (i.e. Ellis Island in the early 1900s) while reading a historical novel about immigrants in their reading class.

The students were broken into literature circles (think reading groups), each of which read one of the following novels:

- Letters from Rifka (Karen Hesse) – the story of a Russian girl immigrating to the U.S. in the early 1900s, a very typical Ellis Island story which most closely related to their history course

- Inside Out & Back Again (Thannha Lai) – the story of a Vietnamese refugee in the 1970s

- Shooting Kabul (N.H. Senzai) – the story of a Muslim family fleeing the Taliban in Afghanistan just prior to 9/11

My goal was to answer a series of research questions to help me understand how these works of fiction impacted their understanding of the struggles immigrants face, especially their ability to think critically and empathize with the immigrant characters.

Data Collection

As a qualitative researcher, I triangulated my data by using three different types of data collection:

- Interviews of students, including a pre-reading questionnaire and then a post-reading interview

- Classroom observation, in which I listened as students discussed the novels in their literature circles

- Document analysis, in which I analyzed the students’ written assignments

Two Key Concepts: Culturally Relevant Literature & Mirrors, Windows, & Sliding Glass Doors

Like other academic research, my study built on the work of past researchers. The following key concepts have become very familiar to anyone working in the fields of reading and education.

Culturally Relevant Literature

If you read ten different educational articles on “culturally relevant literature,” you might find ten slightly different definitions. For the purpose of my dissertation, I defined it as literature in which the readers see themselves and their communities reflected and valued (Fleming, Catapano, Thompson, & Carillo, 2016).

In other words, everyone deserves to see themselves reflected in the books they read. It was not, however, my goal to adopt a narrow definition of “culture” to mean simply “ethnicity.” Culture has many aspects. It can include age, historical time period, gender, language, food, geographic location, and religion. For the purpose of my study, it also included immigration status, i.e. whether someone was an immigrant, first-born generation, second generation, or beyond.

Mirrors, Windows, & Sliding Glass Doors

In 1990, Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop published an article entitled “Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors,” which has become the seminal piece in explaining why we need culturally relevant literature. According to Dr. Bishop, readers might have three different kinds of experiences when reading a book.

First, the book might be a mirror experience, in which the reader sees her own experience reflected. For example, as a Catholic, Italian American living in Chicagoland, I can read Carmela Martino’s middle grade novel Rosa, Sola and have a mirror experience because I can relate to the main character’s Italian culture, language, food, and religion. I would not, however, relate to the girl’s age (10) or her historical time period (1960s).

At the same time, a ten-year-old Irish Catholic girl might not relate to Rosa’s Italian culture, but she would see mirrored in the book her own religion and relate to Rosa as a fellow ten-year-old girl. Both the Irish Catholic girl and I could have mirror experiences with the same book, but in different ways.

Secondly, the book might offer a window experience by allowing the reader to peer into a culture that is different from her own. For example, I have no idea what it’s like to be an African-American teenage girl in the 21st century, but reading a young adult novel like The Hate U Give (Thomas, 2017) can act like a window that allows me to peer into that world for a while.

Thirdly, books can be sliding glass door experiences. In this case, the reader is able to “step through” and enter into the character’s unique experiences. In my dissertation, I offered the example of the middle grade novel Return to Sender by Julia Alvarez (2010). The chapters alternate perspectives and, with each one, we step into a different world. At times we step into the world of a Caucasian boy who can’t fathom why his family has hired undocumented workers to help on the family farm in Vermont. At other times, we step into the world of the Catholic Mexican daughter of one of those undocumented workers.

Participants in My Research

As stated above, I conducted interviews with students in addition to collecting data through classroom observations and document analysis.

My interview participants were 9 eighth graders. For clarity, I referred to immigrants as “first generation,” children with at least one immigrant parent as “second generation,” and grandchildren of one or more immigrant grandparents as “third generation.” My participants broke down as follows:

- One first generation – an immigrant from Vietnam, who had arrived in the U.S. only a few years earlier

- Seven second generation – children with at least one immigrant parent. Countries represented in this sampling included Bosnia, Assyria, Mexico, Romania, Albania, and Poland.

- One third generation – the grandchild of an immigrant from India.

Data Results

Most of what my data found was confirmation of what previous researchers had found through quantitative measures; that is, that students developed greater empathy for real-life immigrants through reading fiction (Vezzali, Stathi, & Giovannini, 2012).

It was no great surprise that the Vietnamese immigrant related to the Vietnamese refugee in Inside Out & Back Again. In terms of culture, language, and food, she definitely had mirror experiences. However, she also admitted to having a bit of a window experience in that she was not a refugee who escaped rather quickly. Rather, her family applied for immigration and waited ten years to get permission to move to the U.S. Fortunately, her family was not the dire straits of the main character in the book, so she was able to peek into the dangerous world of what refugees from her country experienced during the Vietnamese War.

Meanwhile, some second-generation students related the character’s experiences to what they knew about their parents’ experiences. They could almost “see” their parents reflected in the main characters of the stories.

But here’s where things got interesting . . .

Students connected to the main characters in ways that expanded upon previous definitions of cultural relevance. In their interviews, students revealed to me that they related to them in ways beyond just culture, language, and age. Even if they did not share the same culture, language, time period, or generational status as the main character, they still found moments of mirror experiences. They related to how the immigrant characters were often bullied before, during, and/or after immigrating. Not because they were immigrant themselves, but just because bullying is such a prevalent problem at their age.

They also related to similar family situations. Often the main characters had difficult situations with siblings and/or parents, and the students related to that as well. Many of the books involved a character losing or being separated from a family member, and they told me about the times when they grieved the loss of a close relative.

In other words, students were able to relate to experiences even when they did not share a common language, culture, religion, or even time period with the main character.

Things didn’t get really interesting, though, until I looked specifically at those second-generation students. And that’s when I coined a new term . . . .

Crystallizing Experiences

In looking over my research notes, I noticed a phenomenon that I had not seen or read about while completing my literature review. Since seven of the nine participants were the children of immigrants, they had an experience with the novels that combined facets of both mirror and window experiences. In other words, they saw their parents’ experiences reflected in the characters in the novels—almost a secondhand mirror experience. It was as if, in the mirror, they saw their parents standing behind them. At the same time, the novels provided a window experience through which they could peer deeper into the experience of an immigrant and perhaps even understand their own parents’ experiences better.

For example, Avani (pseudonym), the daughter of two Bosnian immigrants, had heard her parents’ immigration stories but confessed that reading Letters from Rifka brought her greater understanding of what her parents had experienced:

When my mom told me the story of her coming here, she only got into detail a bit. She just said she was actually in college in England and then she had to come back for my uncle and my grandma, and she went to America, and she told me a little bit [about] how she came here with like nothing, so I was like, ‘Oh, that must have been really hard,’ but when I read the story, I really kind of pictured what my mom had to go through. I was like, ‘Wow, that’s terrible,’ you know? I’m probably going to ask my mom a little more about it because it’s really interesting.

(Avani, Interview, February 13, 2020)

Avani shared with me how she felt driven to learn more about immigration in general and her parents’ experiences specifically after reading the fictional account of an immigrant’s struggles. I’ll come back to this later when I discuss The Chosen TV series.

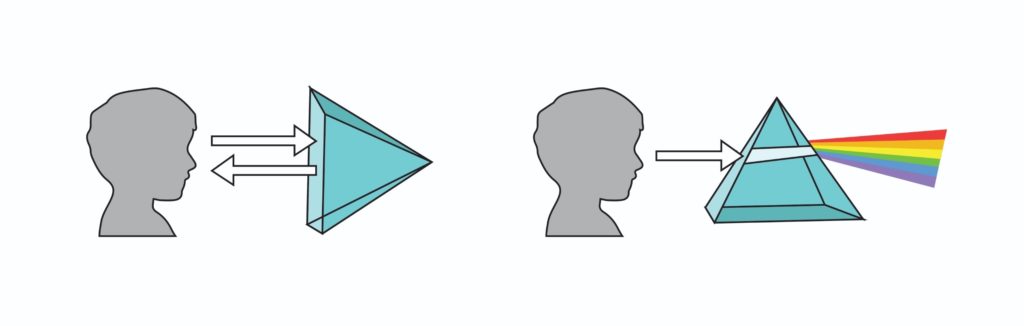

At first, this dual mirror-window experience reminded me of a prism, specifically a triangular, or optical, prism. With a triangular prism, light can hit the glass surfaces in two possible ways. If the light hits it straight on, all of the light is reflected straight back, and the prism acts as a mirror. However, if the light hits the surface at an angle, the light is refracted (instead of reflected) and a rainbow appears. The beam of white light that entered the prism leaves it at varying wavelengths, and the white light expands out into a full rainbow of colors.

The more I contemplated this image, the more it suited the experiences of all the participants. All of them had at least some moments of mirroring. At the same time, they all came to a greater understanding of what it meant to be an immigrant or a refugee. Through the novels, they saw vibrant pictures of what it means to be an immigrant, just like someone sees all the colors of the rainbow when white light is refracted. In that sense, the book took what they already knew about immigration and refracted it for them in a way that brought them an expanded understanding. They could now see, smell, hear, and almost feel what it was like to be an immigrant.

From Prisms to Crystals

Digging deeper into my data, I discovered that these books were able to create this deeper understanding because the authors of these YA novels used a whole toolbox of literary devices (e.g. sensory details, figurative language, first-person narrator or third-person narrators with deep point of view) to give readers the sights, sounds, and emotions of the immigrant experience. In other words, these novels took immigration stories that had previously been “black and white” in the students’ history textbook, or even in their parents’ retellings, and turned them into glorious technicolor movies in their minds.

I returned to my research and discovered something I had not known about crystals. A crystal is “any solid material in which the component atoms are arranged in a definite pattern and whose surface regularity reflects its internal symmetry” (Manan, 2020). In other words, the determining factor in classifying something as a crystal is tied to its internal structure. Just as the atoms in a crystal must be arranged in a particular way in order to make it a crystal, so must the words in a novel be arranged in a certain way in order to evoke empathy in the reader.

Crystals then become prismatic when their surfaces create opportunities for both reflection and refraction. In other words, these books functioned as prismatic crystals. They were able to create both mirror and window experiences that took the students’ understanding to a deeper, fuller level because of the way the words inside them had been chosen and arranged.

These books made clear for the students something they had had a basic understanding of prior to reading the novels. The fiction they read helped to crystallize their understanding. Thus, the crystallizing metaphor works on two levels: 1) to explain how the way authors write their books impacts the ability of the reader to empathize with the character, and 2) to demonstrate how books can reflect and refract the reader’s world in ways that help them clarify their thoughts and understandings.

How does this relate to The Chosen TV series?

As stated at the beginning, I defended my dissertation in June of 2020, which means I wrote the final chapters at the very start of the pandemic. At the time of the initial stay-at-home orders, people were looking for shows to binge on TV and, with livestreamed episodes of The Chosen being shared on YouTube, many more people were suddenly checking it out. (For the record, I binged it in January of 2020. I had just received my IRB approval and had about a week of downtime before I began my data collection in the classroom, which gave me about a week to “binge Jesus,” as they say.)

As more and more people praised this show for helping them to understand Jesus better, I contemplated why this was happening, and I realized that it related to my research findings. The evangelists who wrote the four Gospels were interested in recording history. They were not authors trained in the craft of writing, nor did they need to flesh out in vivid sensory details what life was like in the Middle East 2,000 years ago. Their readers already knew! In other words, they were more like the historians who just tell you what happened without a lot of literary embellishment. Thus, the Gospels can read a bit like a dry history textbook at times.

However, when a talented, modern-day filmmaker like Dallas Jenkins comes along and presents the stories in such a way that the contemporary viewer can now smell the stinky fish on Simon Peter when he returns home from a day of fishing and see the dirt on Jesus’s clothes, the story suddenly becomes more relatable because we can picture it better.

In previous Christian films, Jesus is often depicted as more of an abstraction; his divine nature is brought to the forefront while his human nature is minimized. However, The Chosen, with its scenes of Jesus laughing, brushing his teeth, and dancing at a wedding, reminds viewers that Jesus is both divine and human. It’s as if, for the first time, people are seeing Jesus as a flesh-and-bone creature! He’s become tangible for them.

That is why people are connecting with this show so much—because Jesus and his disciples have suddenly become culturally relevant again, precisely because they are depicted as having normal human experiences. (Remember how I said that the students in my study related to experiences more than any other aspect?) In The Chosen, viewers can now relate to the experiences of Biblical characters. Married couples can relate to both the joys and struggles of Simon and Eden’s marriage. Children can relate to characters like Abigail and Joshua. Anyone who has ever fallen from grace can relate to Mary Magdalene. Any of us who have ever tried to convince a sibling of something can relate to Andrew trying to convince Simon that the Messiah has come!

The same thing occurred with the YAL in my study. The immigrants were no longer abstractions. They were “real” human beings, with normal human experiences, like caring for siblings, grieving the loss of loved ones, and wanting to avoid bullies.

In other words, just as it required the skill of the talented authors who wrote the YA novels that brought immigration stories to life for the students, so has The Chosen succeeded because of the skill of the writers, director, actors, cinematographers, costumers, musicians, etc.

What Can We Learn From This?

I hope my dissertation helps people understand the value of reading fiction, and I hope The Chosen helps people realize that it really is okay to use our God-given imaginations to create works of Biblical fiction, which is sort of a subset of historical fiction.

The novels in my study were historical fiction because they included factual historical events, but they also included fictitious characters. Similarly, The Chosen includes historical facts, events, and people from the Bible while simultaneously adding some imagined (but plausible!) characters, such as Simon’s wife, as well as new (but again very plausible) scenes, such as the Apostles arguing around a campfire.

And what’s the best part of all this? Let’s return to Avani’s quote above. After reading the fictionalized account of an immigrant, she wanted to learn more about immigration issues in general and about her mom’s experience in particular. In other words, the fiction inspired her to learn more facts!

Similarly, many are reporting that watching The Chosen is inspiring them to head to their Bibles to pick out what is actually fact from what is fiction. To be clear, the writers are not altering stories from the Bible, but rather extrapolating upon them and filling in the gaps for parts the evangelists didn’t write down. For example, we know from the story of Jesus healing Simon’s mother-in-law that Simon must have had a wife. However, since the Bible includes no details about Simon’s wife at all, the writers have to use their imaginations to create a plausible wife character for a first century Jewish fisherman.

Personally, I’ve found myself checking details in the Bible after watching the show. For example, the season 1 finale covers the story of the Samaritan woman at the well, a story I like to think I know quite well. (My friend Stephanie Landsem wrote a beautiful work of Biblical fiction called The Well, which is based on that same story.) However, when the woman at the well mentions that it was their ancestor Jacob who built the well, I had thought the writers had inserted that detail. Nope. It was only when I was reading my Bible later that I discovered that detail actually is in the Bible! The writers hadn’t made that one up at all.

So while some may worry that Dallas Jenkins’s show is trying to “replace” or “rewrite” the Bible, I think their worry is unfounded. Reading historical novels made several of the students I interviewed want to ask their parents more about their immigration experiences, and others noted that they were vaguely aware of immigration stories in the news, but now they wanted to pay attention better because their eyes were being opened to the true struggles of immigrants. In the same way, The Chosen is encouraging people to pick up their Bibles because they want to know where factual information drops off and plausible ideas enter into each story line.

Final Thoughts

If you follow me on social media, you know I’ve talked about The Chosen quite a bit in the last year and a half. It’s not just in my dissertation; it’s also in my upcoming book for teachers: Sweet Jesus, Is It June Yet? Some people have asked if I’m on the marketing payroll over at The Chosen, which makes me laugh. No, I am not. I mean, I wouldn’t turn down a role as an extra if Dallas offered me one–but I have enough jobs, I don’t need a new one. 😉

Really, whether I’m talking about TV shows or books or interviewing authors, I pray that my goal is always the same: to inspire people to live as Jesus would and to make sure all I do is for the greater glory of God.

Ad majorem Dei gloriam!

Brief Bibliography

- Alvarez, J. (2010). Return to sender. Yearling.

- Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 6 (3), ix–xi.

- Fleming, J., Catapano, S., Thompson, C.M., & Carrillo, S.R. (2016). More mirrors in the classroom: Using urban children’s literature to increase literacy. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hesse, K. (1992). Letters from Rifka. H. Holt.

- Lai, T. (2017). Inside out & back again. Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins.

- Martino, C. (2018). Rosa, Sola. Arquilla Press.

- Senzai, N. H. (2010). Shooting Kabul. Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers.

- Thomas, A. (2017). The Hate U Give. Balzar + Bray.

- Vezzali, L., Stathi, S., & Giovannini, D. (2012). Indirect contact through book reading: Improving adolescents’ attitudes and behavioral intentions toward immigrants. Psychology in the Schools, 49(2), 148–162. https://doi-org.flagship.luc.edu/10.1002/pits.20621

What a great post, Amy! I find your dissertation research intriguing. Some of your points remind me of the critical thesis I wrote for my MFA in Writing: Striking a Chord: Using Details to Evoke Emotion. Rosa, Sola was my creative thesis for the MFA, so I tried to apply what I learned directly in my work. I’m honored that you mention the novel here.

And I agree with what you say about The Chosen. Watching the series has led to my checking things in the Bible, too. Another surprising outcome of the show: it’s stimulated thoughtful discussion between my husband and me about the actions of some of the characters. While we sometimes discuss Scripture, I don’t think those conversations have the same depth as those inspired by The Chosen.

Thanks for taking the time to share this!